Artist/Maker

John Rogers

(American, 1829 – 1904)

The Slave Auction

1859

Place madeNew York, New York, United States, North America

Painted plaster

Overall: 13 3/8 in. × 8 in. × 8 3/4 in. (34 × 20.3 × 22.2 cm)

Gift of Samuel V. Hoffman

1928.28

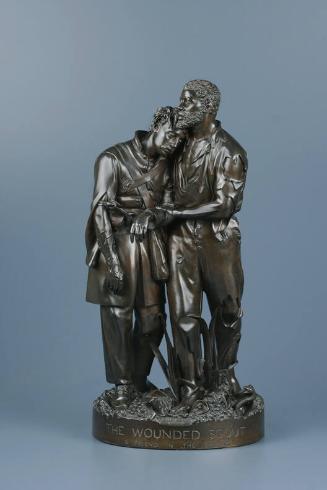

With this small plaster John Rogers burst onto both the art world and the political scene in New York in the months leading up to the Civil War. He boldly depicted a slave auction in progress, illustrating the tragedy of a family about to be torn apart. The father stands defiantly, with arms crossed, and his wife stands on the other side of the podium. Rogers noted that he portrayed her with Caucasian features to suggest that she was of mixed race, alluding to the sexual abuse of female slaves by their masters. She tenderly holds her baby, while her other child, a toddler, hides fearfully behind her skirt. The auctioneer presides over a rostrum with a sign that describes the sale with chilling dispassion: "Great Sale/of/Horses, Cattle/Negroes & Other/Farm Stock/This Day at/Public Auction." Rogers made clear the evil being perpetrated by the auctioneer: his hair forms two curls that resemble the horns of a devil, and what appears to be a tail peeks out from the back of his coat. Rogers himself described the work most vividly: "I have got a magnificent Negro on the stand. He fairly makes a chill run over me when I look at him. . . . The auctioneer I have rather idealized . . . two little quirks of hair give the impression of horns. The woman will be more clearly white and she and the children will come in gracefully. I am entirely satisfied to stake my reputation on it."

Rogers modeled the sculpture while he was working as a draftsman for the city surveyor in Chicago. He had high hopes for the work, expecting it would be "the most powerful group I have ever made." The acclaim it earned in the Midwest inspired him to move to With this small plaster, John Rogers burst onto both the art world and the political scene in New York in the months leading up to the Civil War. He boldly depicted an auction of enslaved peoples in progress, illustrating the tragedy of a family about to be torn apart. The father stands defiantly, with arms crossed, and his wife stands on the other side of the podium. Rogers noted that he portrayed her with Caucasian features to suggest that she was of mixed race, alluding to the sexual abuse of female enslaved peoples by their enslavers. She tenderly holds her baby, while her other child, a toddler, hides fearfully behind her skirt. The auctioneer presides over a rostrum with a sign that describes the sale with chilling dispassion: "Great Sale/of/Horses, Cattle/Negroes & Other/Farm Stock/This Day at/Public Auction." Rogers made clear the evil being perpetrated by the auctioneer: his hair forms two curls that resemble the horns of a devil, and what appears to be a tail peeks out from the back of his coat. Rogers himself described the work most vividly: "I have got a magnificent Negro on the stand. He fairly makes a chill run over me when I look at him. . . . The auctioneer I have rather idealized . . . two little quirks of hair give the impression of horns. The woman will be more clearly white and she and the children will come in gracefully. I am entirely satisfied to stake my reputation on it."

Rogers modeled the sculpture while he was working as a draftsman for the city surveyor in Chicago. He had high hopes for the work, expecting it would be "the most powerful group I have ever made." The acclaim it earned in the Midwest inspired him to move to New York to establish himself as a professional artist. Rogers first offered it for sale at a pivotal moment, just two weeks after John Brown was executed for attempting to capture the federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry in a plan to liberate enslaved peoples. Rogers tried soliciting subscriptions for his sculpture, but apparently with little success. He wrote home in dismay, "I find the times have quite headed me off, for the Slave Auction tells such a strong story that none of the stores will receive it to sell for fear of offending their Southern customers." Rogers had misjudged his audience; he was familiar with the fervent abolitionism of his New England home, and he had not counted on New York's strong commercial ties to the South, which divided the city's sympathies. Undaunted, he hired a Black man to sell the group in the streets, a common means of marketing small sculpture usually practiced by Italian artisans. He attracted the attention of the abolitionist Lewis Tappan, who brought Rogers sales in antislavery circles. The abolitionist George B. Cheever wrote a flattering notice in the Independent. The plaster was acclaimed by other abolitionist publications like the National Anti-Slavery Standard and the New York Daily Tribune.

Meanwhile, Rogers developed a companion piece called The Farmer's Home (no versions are extant). Intended as a stark contrast to The Slave Auction, the group was described as follows: "The hearty, happy father, after his day's work, or on his return from the field, is seated beside his wife, with a laughing baby astride his foot [which he holds] by both hands to be tossed up and down to a tune which the father is whistling. Another frolicking fat urchin is climbing on his shoulder." A dog and kitten complete the contented image. The representation of the Northern family highlighted the injustices visited on the enslaved family. Rogers tried to promote the two sculptures as a pendant pair, taking them to a partner at the New York jeweler Ball and Black. The gentleman "praised them both up to the skies" but admitted that he preferred The Farmer's Home for its "more pleasing subject."

In later years The Slave Auction became an icon of Rogers' patriotism, but it was never a popular work of art. It remained in his sales catalogue until 1866, but the great rarity of surviving examples suggests that few were sold. The group has enjoyed much better fortunes in its afterlife as an image and an idea in public memory and popular culture. Ironically, the image of The Slave Auction was distributed far more widely than the work itself in the form of album photographs, stereo views, and cartes-de-visite. During Rogers' lifetime The Slave Auction was said to launch his career, and he was praised for his moral courage. By 1893 the group was legendary, as one account recalled that it "infuriated" Southerners. It was often called "Uncle Tom's Cabin in plaster," a reference to Harriet Beecher Stowe's literary indictment of slavery.

DescriptionTan painted plaster sculptural group featuring slave parents standing with their two children in front of the desk of an auctioneer who is selling them. The mother is trying to comfort the baby in her arms while her other child hides behind her dress.SignedSigned at center top of base: "JOHN ROGERS / NEW YORK"

MarkingsInscribed at front of base: "THE SLAVE AUCTION"; inscribed on sign on auctioneers box: "GREAT SALE / OF / HORSES, CATTLE / NEGROES & OTHER FARMS STOCK- / THIS DAY AT / PUBLIC AUCTION"

ClassificationsSCULPTURE

Collections

- Underground Railroad